The figtree you now see standing at the end of Davidson Street across from the picnic shelter is a wonderful example of how the trees we plant today comprise our gift to future generations.

The fig is remembered as being planted by famous Australian poet and environmental activist Juddith Wright in the 1980s.

It formed part of the initial 1980s Project Trees bush regeneration works undertaken along Enoggera Creek in a bid to restore some of the vegetation cover that was lost to the area as a result of urban settlement and the need to provide improved stormwater drainage.

In the decade after this tree was planted, the Save Our Waterways Now (SOWN) group formed up and took on the long running and ongoing program to rehabilitate and care for the local creekside habitats.

Revegetating floodplains

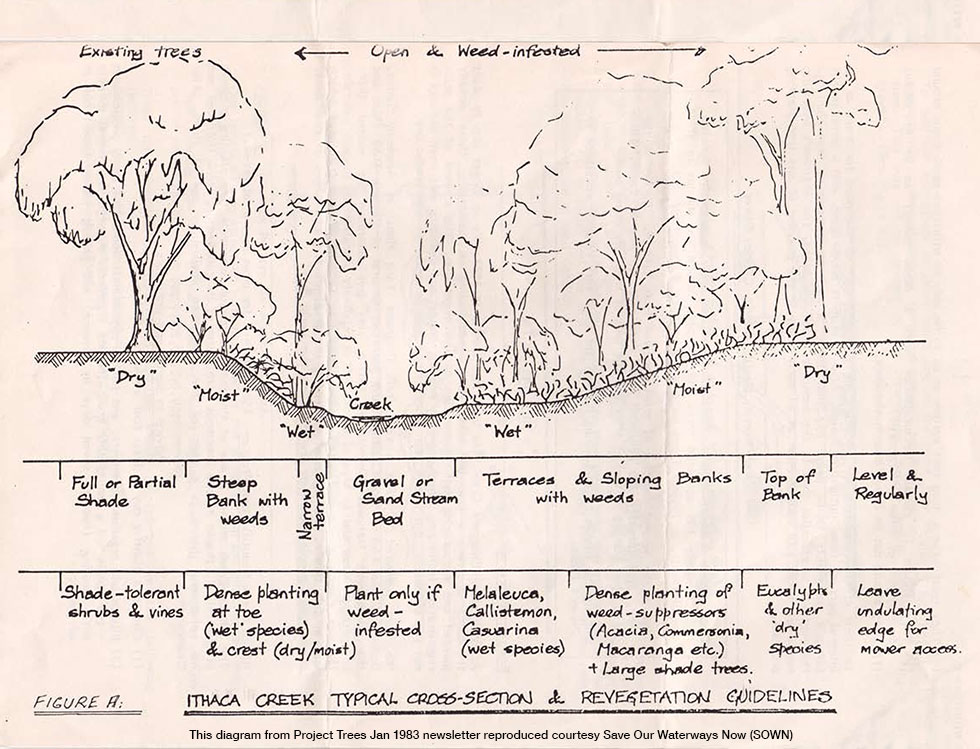

Some understanding of the engineering approach to flood mitigation that contributed so directly to the destruction of creekside vegetation in the 1900s, comes from an absorbing account in the second Project Trees newsletter in January 1983.

Titled "To tree or not to tree - the engineer's dilemma" it describes the constraints needing to be taken into account when intervening on floodplains.

An engineer charged with the responsibility of designing a flood mitigation scheme on a creek through suburbia is, from the inception of the scheme, caught between the devil and the deep blue sea in regard to trees and other vegetation along the banks and flood plain of the creek.

The need for flood mitigation has arisen from over-development of the lower reach flood plains. As part of the development process, trees and ground cover were removed, frequently right to the water’s edge.

Consequently, the stability of the stream banks was decreased, and the banks and flood plain became more scour-prone.

This in turn led to increased siltation and reduction in the flow capacity of the main stream channel, increased flood levels and general environmental degradation.

Against this background of crisis and degradation the flood mitigation design engineer has in the past endeavoured to maintain the developmental status-quo by providing a nearly sterile smooth-banked vegetation-free open channel through the sterile flood plain.

Minimal financial inconvenience to the land-holder was the main external criterion for the design, so that about the only works for which there has been sufficient space was a lined or partly-lined open channel running within a narrow corridor with an absolute minimum of undeveloped land beside it.

Improved hydraulics and lower flood levels resulted, but the ugliness and sterility often remained (or even, in some instances, increased, e.g. Cook’s River in Sydney and Gardiner’s Creek in Melbourne).

The ugliness and sterility of some of the older schemes has now become so unacceptable that the engineer can no longer submit designs which take no account of the environment.

Recognising that any tree-planting will cause some increase in upstream flood levels, the engineer nevertheless increasingly accepts the planting of trees along the banks and flood plains of older channels.

However, care has to be taken to ensure that the enthusiasm of the tree planter does not result in unacceptably increased flood levels.

To their credit, engineers are becoming increasingly aware of the need for trees as an integral part of flood mitigation design. Also it is most encouraging, and a development for any community to be proud of, that there is such an increase in tree-planting.

However, it is essential that in the sensitive creek-side areas, the engineer’s hydraulic needs are taken into consideration at an early stage in the planning of any tree-planting program.